Based on Executive Update Published by Cutter Inc. Full Version Available at https://www.cutter.com/article/crossing-rubicons-agile-transformation-aches-and-pains-implementing-business-agility-502776

Borys Stokalski, Aleksander Solecki

Agile management and delivery practices are becoming a mandatory component of organizations that want to survive the hypercompetitive world of digitally transformed business. Time is precious and so is the capability to handle a continuous stream of innovations and quick responses to unexpected events.

This holds true especially for fast value (product) innovation addressing customer experience and business models. In traditional siloed, command and control organizations, these categories of change require complex, end-to-end processes traversing organizational functions. The capability to systematically execute such changes in an efficient and effective way, with a predictable and sustainable tempo, is what defines true “business agility”.

The end-to-end innovation process starts with ideas that are translated into a backlog of product features and tested in the real market with real clients. Therefore, the productivity of the innovation process depends on the quality of initial ideas as much as (or more than) on proficiency in rushing the backlog through sprints using Scrum or another flavor of agile.

An integrated approach to cope with these challenges should be maintained and synchronized to form an efficient and effective innovation process that provides three essential capabilities:

Julius Caesar was perceived as relatively harmless to the status quo of the Roman establishment while he was out roaming the provinces. He proved his military skills as a successful commander respected by the troops. But this capacity combined with his political aspirations proved to be a deadly threat to the Republic. Once Caesar had crossed the famous river of Rubicon and made clear his intentions to become a first league political figure, he forced decisions upon the key players, who had to choose sides and act upon their choices.

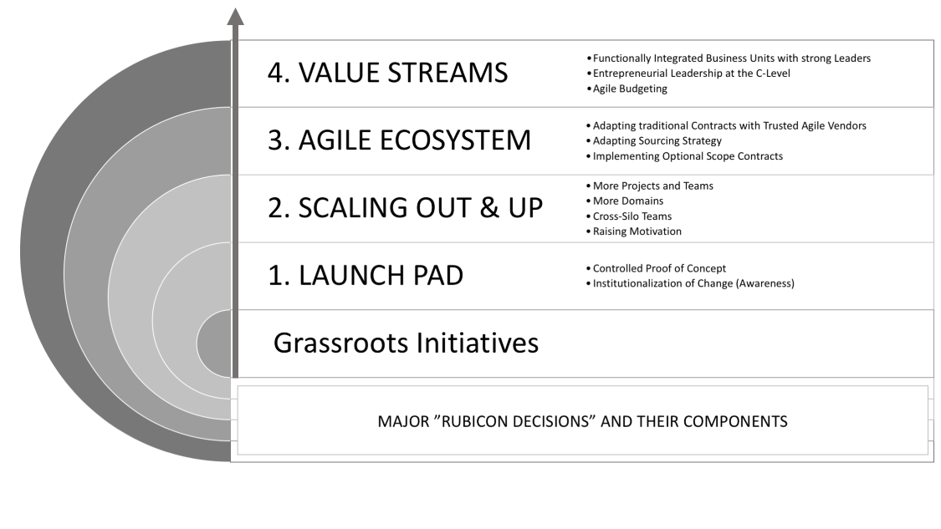

We believe this is a meaningful metaphor describing the challenge of rolling out an innovation that fundamentally changes the way an organization works: an important (and often fancy) transformational concept successfully tried on a small scale, in some kind of sandbox environment, is to be implemented through a large-scale change effort, engaging many new stakeholders. For truly transformative changes that means reevaluation of skills, as well as shifts in priorities, resources, and power. Such a moment uncovers agendas that have remained hidden while the change initiative has been contained and perceived as “one of those ideas” that come and go without much impact on the mainstream of organizational life. In our agile management and transformation support practice we have observed the following “Rubicon Decision” moments in the scaling/extension/rollout of agile (as shown in Figure 1):

Similar decision points often mark an organization’s evolution, from a traditional command and control structure running isolated “agile experiments” at the “provinces” of the enterprise to a consistently agile business.

Figure 1: Rubicon Decisions

Almost every organization has some room for grassroots agile initiatives – projects for which no mandatory process has been defined or organizational units where managers are less interested in how their teams work than in whether they deliver expected results.

Launching an experiment with an agile delivery process is therefore relatively simple. It takes a project, a team motivated to try (or demonstrate) how an agile approach works, and a project sponsor willing either to play the role of product owner or to appoint one. Such a project does not really challenge the status quo; its results are uncertain so even naysayers tolerate it.

Turning grassroots initiatives into an agile launchpad is often the first conscious step in implementing business agility, albeit a relatively simple one. The leaders (usually informal) of grassroots initiatives need to be persuaded to turn their group effort into a controlled experiment and to agree with group members on the scope and goals to be used as proof of process viability (such as performance, quality, or user acceptance). For grassroots teams, such an invitation – if done with respect – is appreciated as an acknowledgement of their contribution to the organization’s success.

What’s in it for me – grassroots teams do “their thing” for their own reasons – usually related to a spirit of professionalism, self-improvement, and sense of ownership of the process. While institutionalization of a grassroots initiative gives its members visibility and potentially also recognition, it takes away some of the ownership.

Conflicting goals – the experimental project has two sets of goals and two scopes. One is related to the product being delivered, the other to the process being used. One needs to be careful that these goals are well aligned.

The experiment may be a totally “grassroots” initiative, owned only by the project team, yet to become a useful launching pad for subsequent rollout it needs to become a “controlled experiment” owned by some part of the organization (such as IT or a business unit) with the intention to evaluate its results and take further action upon them.

The first moment of truth revealing an organization’s commitment to agility is related to the decision to roll out an agile approach after a “successful trial,” a real life project, usually limited in size, that has been executed by a team of skilled enthusiasts.

Too small to fly: some agile initiatives may seem to have it all — a committed business product owner, a skilled team, a successful conclusion — but their goals and scope do not convince people. These projects are perceived as too meaningless to treat them as a reference for change in mainstream project work.

Splendid isolation: grassroots initiatives start in IT and do not involve “real” product owners from business units. Instead, one can find various “product owner proxies” (such as a business domain expert from IT who plays the role of a product owner). Such isolation eliminates the need to negotiate difficult management issues such as the business’s responsibility for and commitment to the project value delivered. The price organizations often pay is a focus on the delivery of features instead of on fulfilling the most important of agile promises – optimized business value of sprints.

Clash of the Titans: sometimes grassroots initiatives expand (mostly in the IT world) even when no one is willing to take ownership for the “UpScaling” decision. Such a situation is relatively rare but may happen in large organizations that employ large development teams. We see recent movement to re-create software development capabilities in banks, telecoms, and even public institutions. People hired to work for or manage such internal software houses often bring with them an agile culture. This leads to culture clashes, which may result in scaling agile practices so that business units embrace them – this usually requires a strong business (preferably C-level) champion of agile.

The first important step is to embrace any grassroots activities and turn them into a controlled experiment that demonstrates the viability of key agile promises – delivering more business value faster and eliminating project work not focused on delivering this value as an unnecessary complication and waste of resources. At the same time, it is important to transparently monitor and address risks that are often brought forward by “naysayers” – such as lack of design, maintainability issues related to scarce documentation, or unreliable performance estimates.

The basic engine of agile transformation is the systematic introduction and ongoing improvement of practices (such as those related to Scrum) at the project team level. This type of transformation, however, must be supported by management involvement in challenging the barriers that organizations discover when attempting the implementation of concepts such as empowerment, business responsibility for project success, transparency, self-organization, a no blame culture, or experimentation.

To cope with these very real, and often very difficult challenges, we encourage readers to use practices borrowed from the ADAPT framework defined by Mike Cohn in his excellent book “Succeeding with Agile”. ADAPT promotes relatively straightforward initiatives, which may create a holistic effect supporting the effective large-scale adoption of agile:

Finally, the agile transformation of a command and control organization is in itself a complex effort, so it makes complete sense to adopt agile principles for this very effort. At a minimum this should mean a shared vision of the organization (a “better us”); an iterative, roadmap driven approach to change; and conscious, controlled experimentation with new practices. This approach helps an organization to learn and allows its own “agile way of life” to emerge from experiment after experiment.

For decades the commercial relationships between companies that provided software development services and their clients have been shaped by either fixed price / fixed scope or time and material types of contracts. The drawbacks of both approaches have long been evident, but, nevertheless, both sides have learned to use them to protect their own interests.

Companies often use both schemes as legal vehicles to experiment with agile processes. Fixed price / fixed scope contracts require a creative approach to contract management so that scope changes are not misused as painful and expensive change request opportunities, and the service provider is not penalized for any unrealized backlog. On the other hand, time and material contracts require trust that the vendor will transparently and adequately perform its effort calculation for backlog items and will not use a backlog as an opportunity to increase its margins. This kind of trust and mutual understanding can exist with select trusted suppliers (and, equally, with trusted customers), but building an agile ecosystem is a different story. An agile ecosystem requires the creation of a systemic setup that works with the market and not just selected vendors. This is why we believe it is a “Rubicon decision point”.

Supplier shakedown: not every vendor has the capabilities to provide services using agile processes. It is not just the process skills. The economics of fixed price contracts are often used by competent vendors to generate margins through economies of scale and cost management on the delivery side. As long as the price / quality remain competitive and delivery does not suffer, there is nothing ethically wrong with the arrangement; in fact, this capability is often based on good organization, domain experience, and/or mature reuse practices. More frequently used are optional scope agreements – attributed to Kent Beck, and widely accepted as a model for agile project contracts – which imply a lot of transparency related to estimations and team composition. The vendor can not use his structural capital and knowledge and is often forced to compete on the basis of a team “blended rate”. This type of contract benefits small shops or outsourcing companies and puts companies with developed structural capital at a disadvantage, eventually leading to a rapid, radical change in the supplier portfolio. This may or may not be a benefit for the organization, so this effect should be carefully managed.

Legal affairs: the framework contracts and standards for services / solution procurement are most likely aligned with the fixed price / fixed scope or time and material approaches. They are also most likely driven by risk aversion as far as scope management is concerned, which will inhibit the adoption of optional scope agreements for contracting services based on an agile approach.

Unfixing the scope: a challenge for decision makers is to avoid a deeply rooted, fixed scope mentality. It resurfaces often in situations where a decision maker, even an agile-friendly one, who has not been involved in the project on a daily basis, faces a situation where the results of an agile project diverge from the original vision. The real question is whether this departure from the original scope has been conscious and well managed by an empowered product owner. If so, then most likely the expectations at the inception of the project were unrealistic or simply wrong, and the agile process has helped the team to discover the wrong expectations and adjust them. But some decision makers tend to perceive such a situation as a failure to “keep a project on track”, and so demonstrate lack of trust toward the supposedly empowered product owner, undermining his or her authority.

Optional scope contract schemes, the most advantageous for agile projects, should create room for flexibility and experimentation. This purpose is rarely served well by hundred-page framework agreements that focus parties on avoiding risks instead of on delivering value and experimenting. If there is no room for trust and a bona fide approach to vendors (and vice versa), there is probably very little room for agile cooperation. Legal departments are instrumental in determining what the right legal tools are for the job and must share responsibility for achieving the goals of transformation.

Optional scope as often practiced today defines the general terms for work performed in short increments (ranging from a single sprint to 3 months). The terms usually include team composition, quality criteria, and agreed procedures for team, budget, and backlog management. This allows for reasonable scope flexibility within each increment.

An agile-friendly legal setup balances the risks on the client side (the client can have clear expectations related to near-term project results) and on the supplier side (the supplier has clear near-term obligations but does not take the risk of estimating a budget for an unclear scope). An additional risk for both sides is that the supplier may not be contracted for the following increments, but it seems that mitigation of this risk is relatively simple. The client should build a portfolio of suppliers for specific domains (a master supplier and a challenger seem to be the minimum) but is also well motivated to treat suppliers in a fair way. Suppliers are likewise motivated to treat clients fairly. Or at least those who seek long-term engagements, which are usually more profitable due to lower sales and transaction costs, have good reasons to provide customers with rational estimates, reliable delivery of valuable results, and better than average productivity.

It should be noted that fixed price contract practices may also be effectively used in agile projects. A reasonably simple, transparent, and reliable practice to measure the size and effort of scope changes is a valuable support, as well as risk budgets that can be used to embrace more substantial changes without contract renegotiation.

A similar remark applies to time and material contracts. They can be used quite easily as a legal solution for agile projects with the acknowledgment that as all the scope management risks are on the client, one should primarily use time and material contracts with known, trusted suppliers. In such a situation, the flexibility afforded to build truly interdisciplinary teams by mixing just the right pool of skills and talents from both the suppliers’ and the client’s sides may be unparalleled.

Value streams are business architecture patterns essential for business agility. They require a governance model that radically departs from that common in command and control organizations and moves towards one with decentralized yet efficiently coordinated business units integrating decision and operational processes. In addition, this governance model should integrate product innovation with business development and operations and effectively dismantle organizational silos. The rationale is that, in hypercompetitive markets, the efficiency of horizontal processes (such as turning a new product idea into a well performing marketable product) has more impact on overall business performance than does the functional efficiency of silos. (Note that we discuss agile budgeting, a component of mature value stream architecture, below.)

The innovation process is best executed in teams that share responsibility for business results and innovation efficiency. “Value stream oriented” governance is often typical for “pure digital” companies (business which have digital product offerings and fully digitized key business processes). Value streams integrate business domain and technology specialists and are granted autonomy and the responsibility for a part of the company product portfolio. An interested reader will find more on the subject in the article “All the World is a Sound Stage” from Cutter Business Technology Journal on digital transformation.

As we see it, the value stream Rubicon is the most important one to be crossed in the agile transformation journey. It is also the step that potentially delivers the most business value.

Tear down the walls: IT is by far not the only silo in the organization. Integrating functions such as sales, marketing, and customer support into single units responsible for the business results of the product portfolio is even more difficult than integrating IT and non-IT functions.

Leadership deficit: value streams can only be successful when managed by people with specific leadership qualities – such as those who build their authority through empowerment and collaborative practices. Such qualities are often hard to find in command and control organizations, especially those that have been internally very competitive. Internal competition is a killer of agile culture.

Building the commons: decentralization makes it much harder to share resources across value streams and create economies of scale even in relatively simple processes. In a way, value streams become “new silos” – only this time these silos are directly responsible for the market success of the organization.

Time for governance: the role of top executives changes – as the value streams become proficient in business development and operations, the executive jobs will become similar to those of the management of a holding company consisting of independent businesses. Top executives need to focus on governance, leadership development, and strategic issues (such as M&A strategy) and much less on command and control. This change in focus may represent a significant problem for some senior executives.

A good start is to expand project teams to include skills and perspectives other than the strictly technical or managerial (e.g., product marketing, business development, operations). Making such setups a habit is a good start toward value streams even in traditional siloed organizations.

Aggregate functional responsibilities at the board level – so that senior executives take responsibility for business areas covering all the primary required functions, such as product marketing, sales, and customer support. An example might be the appointment of executives responsible for markets, with distinctive client and/or product portfolios. This does not exclude responsibility for the broadest functions such as strategic/brand marketing or financial management. But functions specific to product/client lifecycles can very well be assigned to single executives and in this process tailored to product/client specifics.

It is important to complement value streams with “horizontal” structures that deal with processes and assets that perform better when shared across value streams. We find a growing number of initiatives implementing such a business architecture in digital media, banking, and telecommunications. Such horizontal structures include:

Agile budgeting contributes to successful implementation of a value-stream-based architecture. The established project budgeting practice is founded on two cornerstones: investment accounting and portfolio management. Investment accounting takes care of capex allocations so that capital is efficiently allocated to projects that offer the best mix of return indicators. Portfolio management takes care of priorities, strategic alignment, and risk management of the company resources (beyond capital). As portfolios are managed by high-level executives, the projects within them tend to be rather complex and long.

From this perspective a project is born when the plan and associated performance indicators are accepted, and finishes when the final product is delivered, at which point the depreciation of invested assets starts and the project dissolves into the opex component. Poor project performance is mostly recognized only through the delays and scope changes that affect cash flows. Product performance is usually disjointed from project performance.

Agile budgeting in the value streams is different. It is about products, rather than projects, forming the value stream portfolio. A product can already exist and generate value or can be an innovative idea that may turn into a component of the value stream portfolio. In the first case, the product has some kind of revenue stream, operational costs, and (hopefully) profit margins contributing to cash generation. The product (or portfolio of products) also has a backlog of changes that affect its market performance and operational efficiency. Such a backlog can include important activities, such as refactoring, that are often very difficult to justify in traditional budgeting practices. A value stream perspective offers much better judgement concerning the value of such backlog items.

If the product does not exist (is an innovative idea), it will most likely be built as a “minimum viable product” by some part of the existing product team. It will then be included in the portfolio and developed through the process of validated learning, based on market feedback. Generally, instead of managing a large, long, complex project, the organization distributes the work into significantly smaller chunks (“epics” and “scrums”), delivering product-related backlogs.

Thus, it seems to make much more sense to replace project budgets with a product development budget, representing part of value stream operational expenditures and serving as financial capacity to be used to meet the business goals of the value stream. The job of senior management changes. Instead of taking decisions on large, obscure projects represented mostly by high level goals and financial indicators, they need to focus on managing value stream performance and empowering their leadership teams to manage product development budgets efficiently.

The projects that remain are the ones that truly benefit from a C-level perspective – strategy management, company acquisitions, territorial expansions, creation of new value streams, and R&D investments.

It is important to understand that opex / capex related indicators are an established way to assess company performance from the perspective of investors. For example, infrastructure-based businesses, such as communication services providers, have better valuation when their opex ratios are low, and capex levels demonstrate their ability to innovate and keep their infrastructure in line with growing demand and quality expectations. Agile budgeting tends to increase opex by allocating to opex a (potentially substantial) part of project costs, which would in other circumstances become capital expenditures. In the long term, opex should normalize as less capital will be depreciated in future. But initially the change in budgeting approach may create a hard bump in investor relations, one that represents another important Rubicon to be crossed.

Certainly the change in budgeting has to be very well communicated to the stakeholders before it is executed. It may be a wise move to actually invest some additional effort to run double accounting for a limited time and to demonstrate the evolution of company performance using both the old and the new perspectives.

In no way should the product budget allocation be viewed as the “money spent”. The actual allocation of resources should strictly follow the business results of the value stream, so rolling forecasts and fast access to performance information are important prerequisites.

The practice of agile budgeting is rooted in the competences of the product owners. Developing their business management skills provides a good basis for implementation of agile budgeting practices in a way that minimizes risks for the organization.

An interesting example may be how north European banks, such as DnB, implemented Beyond Budgeting practices (www.bbrt.org) – one of the first holistic concepts of an agile business architecture. Apart from replacing formal hierarchies with distributed, networked, collaborative teams, the new approach advocated abandoning fixed, annual budgets in favor of rolling, relative performance goals based on internal and external performance benchmarks, with resources allocated on demand. As a result, reporting practices depart significantly from the standards to which stakeholders are accustomed, so pioneering financial institutions had to invest significant time and effort in educating stakeholders about the goals and means, until the long-term benefits could be appreciated firsthand.

Agile transformation often starts as a grassroots experiment of “doers” but cannot deliver the most valuable results – increased business agility – without involving company management who face some bold decisions. The “Rubicon Decisions” we have described in this report can be viewed as generic milestones on an agile transformation roadmap. This roadmap is advanced by increasing the scale of agile practices, experimenting with various aspects of agile processes and components of agile’s cultural background, and refactoring the business architecture around successfully established agile practices and business capabilities.

For sizable organizations with a long command and control tradition and well optimized operations this is no easy task. Some attempt it by greenfield initiatives – building the new organization in parallel with the existing one. Some embark on the road of internal change. There is no single proven recipe for success. But understanding the key Rubicon decisions, after which “nothing remains as it used to be,” supports an honest, risk aware approach to the process. We believe that this kind of integrity is the cornerstone on which agile transformation success becomes more probable. Integrity and walking the talk are essential in the process of transformational change.